The following has been re-posted by Animal Fire Rescue for educational purposes.

The original post can be found at: https://rigginglabacademy.com/what-if-trees-had-ratings-in-kn-tree-anchor-ratings-based-on-wind-loading/

Tree Anchor “Ratings” Based on Wind Loading

What if trees had ratings? What an amazing concept. John Morton, an engineer-scientist-visionary-technician, has been doing canopy studies for years and knows how they are affected by wind. Trees, whether alone or in community, are all influenced by wind and all have a certain “wind rating” to them. When SAR members show up on scene, and these trees are the “anchors of life”, it’s best to know what you working with, right? John does an amazing job at bringing an illuminating view to this concept in his study, “What if Trees Had Ratings in kN?: Tree Anchor ‘Ratings’ Based on Wind Loading”. We hope you enjoy this study as much as we did.

Rigging Lab Academy is all about sharing the story of this planet’s Thought Leaders, and what John has to say is important. The following study was presented by John Morton at the International Technical Rescue Symposium (ITRS) in November 2015. For the full slides of this presentation, courtesy of ITRS, click here.

About John

Since 1999, John Morton has been a technical rescuer with Snohomish County SAR and Everett Mountain Rescue in Washington State. Along with hundreds of rescue missions, John has been an instructor for many basic rescue topics through the years (medical care, fieldcraft, search tactics, working in terrain, etc.). More recently, he spends more time instructing in our technical rescue specialties (rope, water, helicopter). John has been a SAR rope rescue instructor since 2001, and lead rope instructor since 2004. Beginning in 2001, John has been an active member of Snohomish County’s Helicopter Rescue Team, flying as “first out, last back in” Helicopter Rescue Technician. Through the past decade, John has been serving as team leader for our SAR Water Rescue program, including as evaluation hovercraft pilot and as one of our Rescue Swimmers. Beyond rescue work, John is also an avid paddler and sea kayak instructor. And trail running, and skiing, and a few others. When not doing rescue work, or paddling, or working with his trees, John has a little side gig doing airplane and spacecraft design work as an engineer at Boeing.

What if Trees Had Ratings in kN?: Tree Anchor “Ratings” Based on Wind Loading

When technical rescuers arrive at a scene that may involve rope access, among the first things we do is evaluate potential anchors for useful location and adequate strength. Most us have been taught (and then perhaps repeated as instructors) that adequate anchors are foundational to a safe and effective rope rescue system. Most of us have been taught (and then perhaps repeated as instructors) that a living, well-rooted tree is an adequate rescue anchor, provided the trunk is helmet-sized or larger. Specifically, a helmet-sized tree has sufficient strength to withstand forces we might apply via our rope system.

Ideally, it would be convenient if each tree had a carabiner-like “strength rating” placard clearly indicating how much anchor loading that tree is known to withstand. While we are dreaming, it would be even better if that tree’s load capability were demonstrated by testing, since trees do not have tight manufacturing controls. Rather than a test-based strength rating, trees just have this often-repeated “rule” that helmet-sized is strong enough. But is that really all we have to judge tree strength?

People who spend time outdoors will sooner or later witness a group of trees bearing the onslaught of a powerful windstorm. When we watch our wooden giants getting rocked by the wind gods, it is a compelling and humbling reminder of the small scale we humans typically experience. A technical rescuer might watch such a wind storm and think something like, “Wow, those trees are handling forces far, far beyond anything we can bring to bear using our puny little rope systems.” Hmmmmm…

How much wind would a tree need to withstand to show itself adequate to carry equivalent loading that might be applied through a rescue anchor? That probably depends on the type of tree. And how tall is the tree. And what nearby trees deflect some of the wind. And soil conditions. And terrain. And root structure. And perhaps other things that might be difficult to nail down.

When technical rescuers arrive on scene, we can be confident of two things about a living, standing tree: 1) the tree has been exposed to some amount of wind, and 2) the tree has been able to withstand the forces resulting from that wind. If our rescue teams had some method to translate a tree’s strength that has already been proven by wind into equivalent anchor strength (a “wind rating”), then we could make a reasoned decision about using or not using a candidate anchor in our rope system. More anchor choices. Favorable placement for rope alignment. Less rope stretch using anchors closer to the edge. Faster setup. These and other reasons motivate us to consider the widest array of credible rescue anchors.

But to be practical, a method to determine “wind rating” would need to be appropriate for field use. It would need to work with a range of rescuer fluency, and when applied under the time pressure, weather, fatigue, and life safety conditions that define our missions. Anchor selection during a rescue cannot deteriorate into scientific research on scene. No committees. No magic. Plenty of margin. Certainly, this method includes some complexity: mechanical engineering, and numerical modeling, and meteorology (weather), and dendrology (trees), and perhaps some testing (measure and break things). However, the objective of this project is simple: develop a mission-appropriate method that gives go/no-go adequacy of “smaller” trees for use as rescue anchors.

Understanding How a Tree Tells Us What Anchor Strength it Has

Long before our rescue teams arrive to consider a tree as a potential rescue anchor, that tree has been exposed to a variety of natural forces. Depending on climate, a surviving healthy tree will have tolerated effects of wind, precipitation, snow loading, impact from tree or rock fall, etc. As a surrogate for forces applied by a rescue anchor, wind force has the advantage of imparting substantial bending/shear load, much like a rescue anchor would apply. Also, characterizing wind loading on trees can draw on techniques related to predicting wind effects on man-made structures, such as skyscrapers or antennae.

The heart of this project is a force model that has three key elements:

- Determine how much wind reaches a particular sized “smaller” tree.

- Determine the force applied to a tree by the wind that reaches it.

- Translate force from wind into equivalent force applied by a tensioned rescue anchor.

Three additional elements enable the force model and compile useful results:

- Establish an aerodynamic profile for trees that are anchor candidates.

- Calculation tool to examine a range of tree size, over a range of wind speed, for many tree species.

- Produce results that can be consumed by rescue teams, including during an active mission.

Previous work has established that detrimental effects on trees used as rescue anchors are primarily related to bending and shear load that compromise the base and root system. Other theoretical failure mechanisms, destruction of the wood itself, for example, are not what limits our ability to use a particular tree in a rescue system. Rick Weber, “How to Determine Tree Strength”, ITRS 2010.

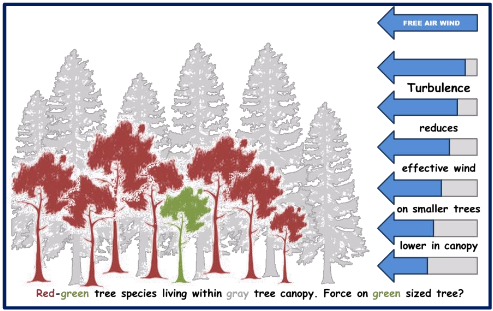

Turbulence Model: How Much Wind Reaches a Smaller Tree?

Modern weather-related data gives fairly thorough indication of wind throughout a region. Example access points might include National Weather Service websites, Weather Underground, and various aviation weather resources. During seasonal high wind events, the upper end of sustained wind speed is shown here as “free air wind” speed. Wind speed in free air is related to, but not the same as the wind that impacts smaller trees within a canopy. Lower in the canopy, wind speed, and the resulting forces are reduced as the moving air becomes turbulent.

In addition, the speed of turbulent air varies within the canopy, such that the wind speed towards the top of a mid-sized tree is not the same as further down that same tree. Finally, a tree species may be intermixed with other taller species, so that the canopy is determined by trees taller than a full-sized example of the species under consideration. For purposes of force calculations in this model, turbulent wind below the canopy is “sliced” into decreasing wind speeds moving lower in the canopy.

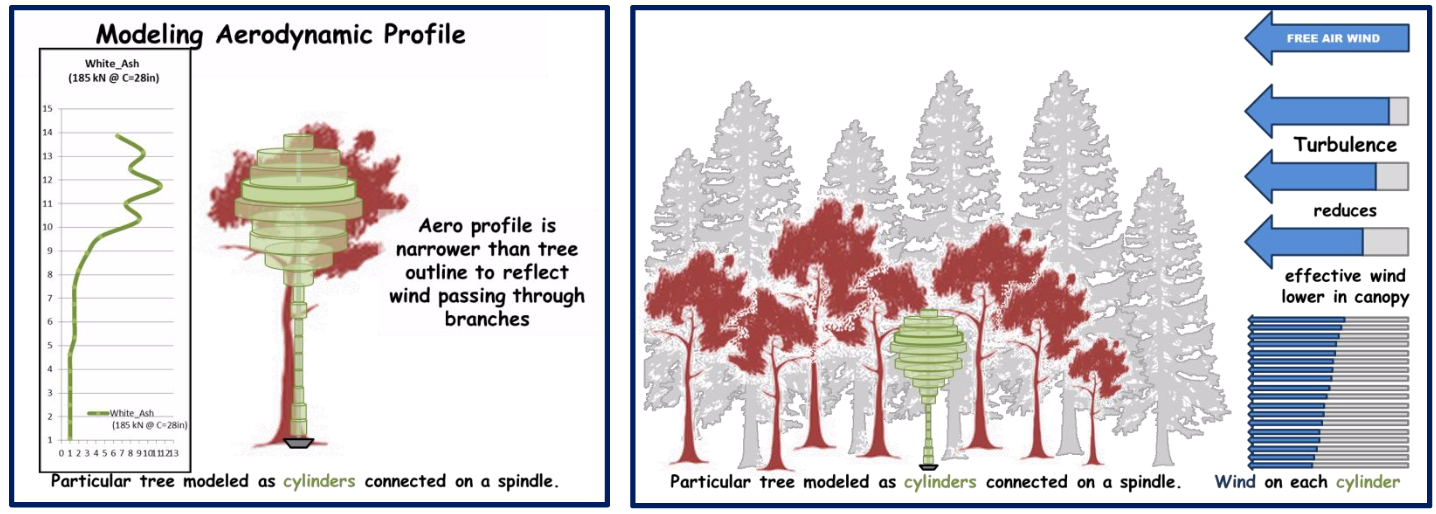

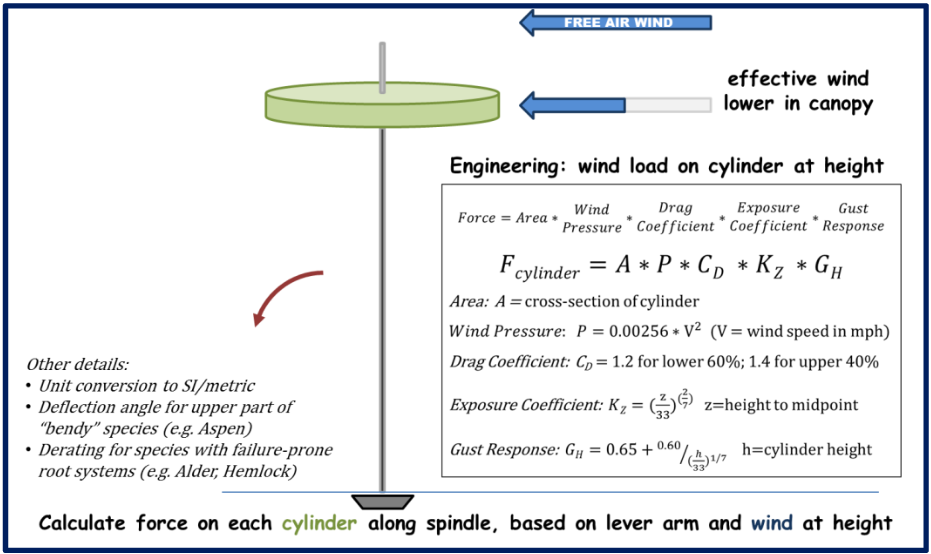

Aerodynamic Profile: Representing a Tree as a Stack of Spindled Cylinders

There is considerable variation among individual real-world trees–even of trees of a single species. For this wind force model, a species tree is simplified as a representatives tack of 20 cylinders on a spindle anchored at its base. Each cylinder represents 5% of the tree height, but is narrower than the tree outline in order to conservatively address variation among individual trees. In the crown portion of the tree, the diameter of the cylinders are well within the tree outline to represent wind passing through branches with comparatively less force on the base.

Tree species data in the model also include a relationship between base circumference and tree height, as well as canopy height of neighboring species. Where there is variability, such as canopy height of neighboring species, profile data are chosen conservatively. Tree shape parameters and information about neighboring species (canopy) are drawn from references such as United States Forest Service Silvics Manual, and the Audubon Society Field Guide to TREES.

Engineering Magic: Calculating Wind Force on Cylindrical Structure

Once a turbulent wind profile and aerodynamic tree shape are established, they are aligned at ground level. Then force is calculated for one cylindrical segment at a time. Wind loading on a cylindrical body at height (reacted at its base) is well understood from design of skyscrapers and antennae. While the calculations have somewhat complex exponential terms, the relevant formulae are readily available, even just a Google search away. Here’s one example, among many.

Once a turbulent wind profile and aerodynamic tree shape are established, they are aligned at ground level. Then force is calculated for one cylindrical segment at a time. Wind loading on a cylindrical body at height (reacted at its base) is well understood from design of skyscrapers and antennae. While the calculations have somewhat complex exponential terms, the relevant formulae are readily available, even just a Google search away. Here’s one example, among many.

The base of the tree carries wind load accumulated over the entire tree length, demonstrating the tree’s ability to carry bending and shear force. This is the same load carrying capability we rely upon for a rescue anchor.

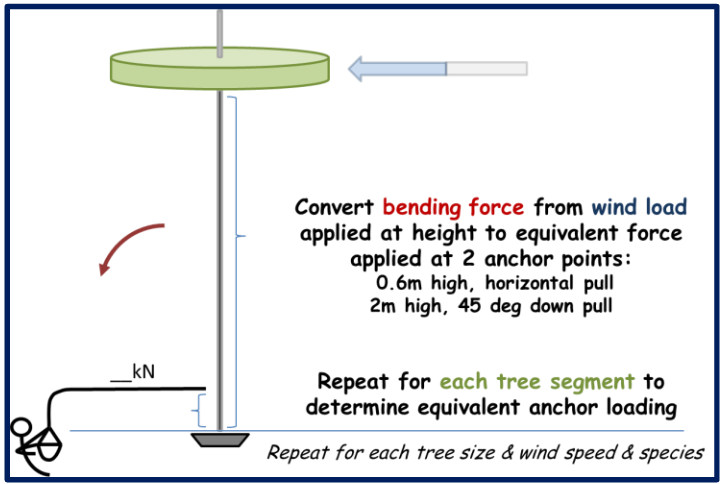

Mechanics: Translate Wind Force into Equivalent Anchor

Perhaps the most straightforward part of this project is translating force applied to a tree at height to an equivalent force applied at the location of a rescue anchor. This translation is calculated segment by segment, using techniques that would be familiar to a mechanical engineering student.

It is worth noting that these calculations correlate wind force over the entire tree length to an equivalent anchor force applied horizontally at a height of 0.6 meter (2 feet). This is deliberately not as low as a rescue anchor could be placed on a real-world tree. Moving an anchor lower on a tree provides on-scene rescuers an option that adds margin beyond these results. Depending on risk factors, placing an anchor very low on a tree may allow responsible use of an anchor that calculates as “marginal” at 0.6 meter anchor height.

It is worth noting that these calculations correlate wind force over the entire tree length to an equivalent anchor force applied horizontally at a height of 0.6 meter (2 feet). This is deliberately not as low as a rescue anchor could be placed on a real-world tree. Moving an anchor lower on a tree provides on-scene rescuers an option that adds margin beyond these results. Depending on risk factors, placing an anchor very low on a tree may allow responsible use of an anchor that calculates as “marginal” at 0.6 meter anchor height.

A similar set of results is compiled that correlates wind force over the entire tree length to an equivalent high directional anchor force applied 45 degrees below horizontal at a height of 2 meters. Once again, this is conservative as a typical high directional pulls more vertically than 45 degrees. Here also, on-scene rescuers have the option of placing high directional anchors lower than 2 meters if that helps a marginal strength tree.

Number Crunching: Repeat for Each Tree Segment, Tree Size, Wind Speed, Species

It would be possible to hand-calculate the turbulent wind profile under a species canopy, then identify the resulting wind impacting a “modeled tree” cylindrical segment of particular height and diameter. Then one could calculate the wind forces applied at the lever arm that is the height of the cylinder above the ground. Possible, but tedious to hand calculate.So, we will leave that to the computer.

This project includes a rudimentary computer program to repeat the wind loading calculations for 20 segments per tree. Then the cycle is repeated for each increment in tree circumference for that species. Then that entire calculation for various tree sizes is repeated over a range of free air wind speed. Then the size/wind speed cycle is repeated for each tree species of interest.

As the calculations repeat for increasing tree circumference, the 20-segment aerodynamic tree model is scaled accordingly. This extends the slightly taller tree model higher into turbulent wind, as well as exposing slightly wider cylinders to that wind. Both factors tend to drive increased wind force, though the relationship is not linear – for example, a 2% increase in tree size results in more than a 2% increase in force applied to the tree.Likewise, a 5% increase in wind speed results in more than a 5% increase in force applied to the tree. The details are complicated but manageable in small steps.

As the calculations repeat for each wind speed, the turbulence model is adjusted and calculations repeated over the range of tree sizes (circumference in inches). As the calculations repeat for each tree species, the associated canopy determines the turbulence profile that applies.

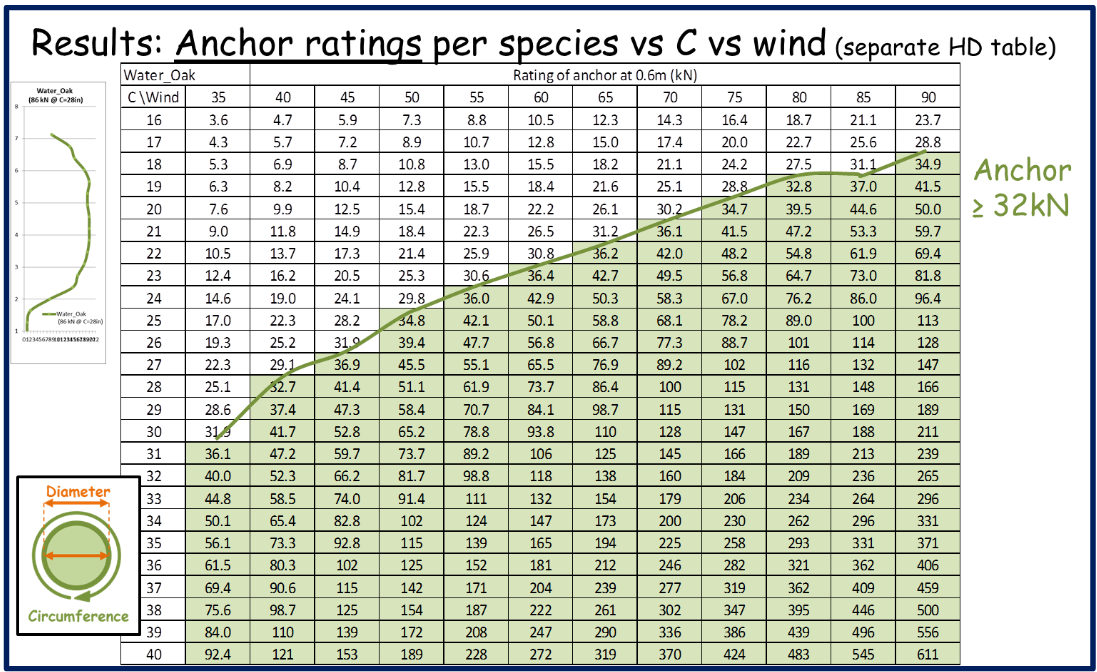

For each tree species, the calculations result in two tables listing anchor strength values for a range of tree size and wind speed. One table is for a horizontal rescue anchor set at 0.6 meters, and another table for high directional set at 2 meters and pulled 45 degrees below horizontal. From these force data, a variety of tables and charts are built to be applied by rescue teams.

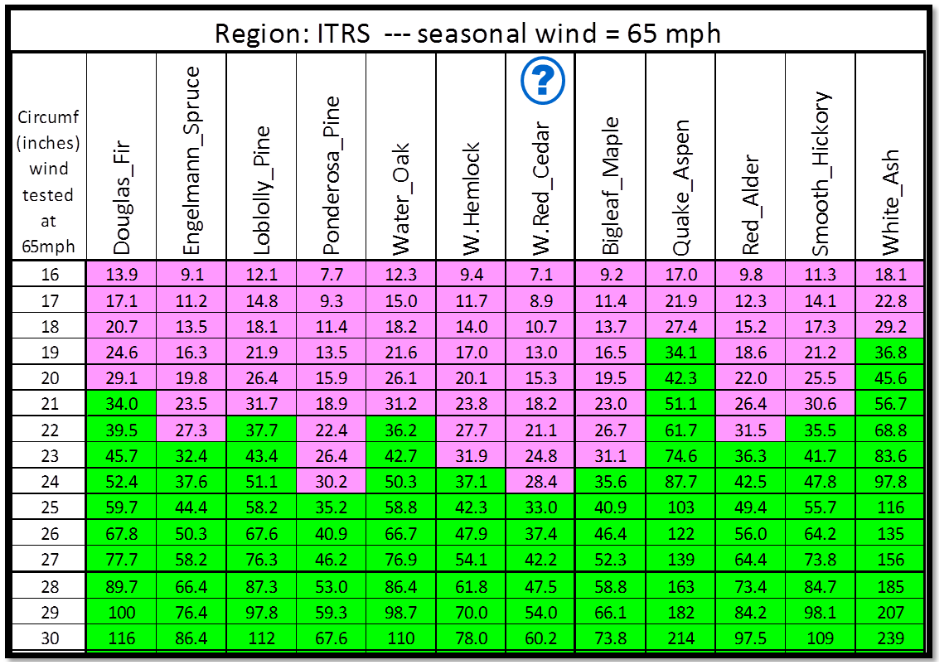

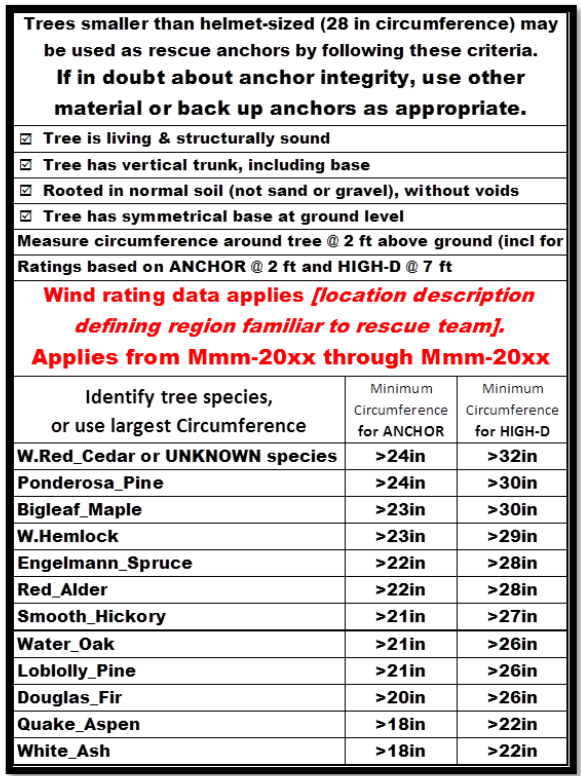

Results: Collect the Data in Various Formats, Including Field-Deployable Guides

The model output collects results for up to 12 tree species per designated region. Results include material that enables“sanity checks” –data not intended to be field deployable. One example shows full-strength anchor size vs wind speed for 12 tree species (below).

But the most valuable results are pages that can be included with field gear that enables rescue teams to make go/no-go anchor decisions on scene (below).

The inputs required to produce region-applicable “field guides” include free air wind speed (typically upper end of sustained wind during storms) and also the threshold of choice for rating of a “full strength” rescue anchor.

For the purposes of illustration, these results show a fictitious “ITRS2015 region”, which includes a sampling of trees from across North America. To create sample field guide pages, these results were run with a “rating” of 65 mph as free air wind speed, and 32 kN as threshold for a full-strength anchor. Note that these inputs do not affect the tree or wind models, nor on the force calculations for various sized trees. Rather, these fully-adjustable inputs only determine which results are collected into field guide pages.

For the purposes of illustration, these results show a fictitious “ITRS2015 region”, which includes a sampling of trees from across North America. To create sample field guide pages, these results were run with a “rating” of 65 mph as free air wind speed, and 32 kN as threshold for a full-strength anchor. Note that these inputs do not affect the tree or wind models, nor on the force calculations for various sized trees. Rather, these fully-adjustable inputs only determine which results are collected into field guide pages.

There must be some time element to these results. Wind that a tree was exposed to 10 years ago is not a compelling indicator of that tree’s strength today. In the Pacific Northwest, our seasonal wind events are typically in December through March. Our SAR team expects to update these field guide pages each spring, based on winds during the preceding months. Then the results are considered valid for about 1.5 years (through two summer rescue seasons).

It is important to note that wind rating values do not indicate true breaking strength of a tree. Rather, they show an anchor force the tree can withstand based on wind forces the tree has already withstood. A tree may be considerably stronger than these values suggest. This is particularly true for triangular-profile trees, such as Western Red Cedar. These have a fairly thick trunk for their height, and most of their sail area is low to the ground.For example, in the same wind storm, wind force on a 20-inch circumference Red Cedar would be less than a 20-inch White Ash. Yet the Red Cedar may, in fact, be stronger than the same sized White Ash, just not as thoroughly tested by wind forces. While the additional strength beyond the wind rating is difficult to quantify, the margin is in the direction of safety.

To be useful, this method to determine “wind rating” needs to be appropriate for field use during a rescue mission. It needs to work with a range of rescuer fluency, and when applied under the time pressure, weather, fatigue, and life safety conditions that define our missions. It has to be repeatable by different team members and on different days. It has to fit into normal team training.

Printed on two sides and laminated, this field guide has a simpler side, and an almost-as-simple reverse side. Using the super simple front side, a rescuer armed with the laminated page and 3-foot tape measure can consistently determine go/no-go for a prospective anchor tree. The ability to distinguish species improves tree options, but is not critical to consistent go/no-go decision.

Using the reverse side, and armed with the tape measure, a sharpie, and some pink and green flagging, a team could send New Guy ahead to measure and label candidate anchor trees in the operational area. Flagging would indicate go (green) vs no-go (pink), as well as strength ratings in kN. This would literally result in anchor trees having the physical equivalent of a rating stamp like a carabiner or pulley. More practical for a real rescue mission, an individual tree’s “wind rating” could be looked up, so that anchor decisions can be made in seconds (use it, back-tie, multi-point, don’t use it).

Critical Thinking: Do the Model Results Seem Reasonable?

Based on extensive pressure testing, this wind force model yields consistent and sensible data. The results compare well to analytical and test data, make sense when comparing one species to another, and also fit anecdotal experience using smaller trees as rope system anchors. As I have previewed the model results with experienced technical rescuers, several questions are frequently asked.

Q: Why 20 tree segments, rather than more or fewer?

A: I tried as few as 12 segments for trees, with marginal results as tree shape nuance had noticeable effect on results for a given wind speed. I also tried more detailed profiles such as 30 or 40 segments. These aero profiles are more difficult to create, yet had little effect on results, compared to 20 segments.

Q: How do model results compare to testing?

A: Rick Weber’s work presented at ITRS-2010 is an example of past study and testing showing tree anchors into the 15 kN range. This is excellent data, and responsibly tops out when real-world forces begin to pose problems during testing. Once calibrated for anchor height, these test data line up very nicely with model results described here. Such alignment is not conclusive, but it is compelling.

Q: Does this mean rescuers need to learn tree species identification to do their job?

A: If rescuers cannot identify the species of a candidate anchor tree (limited by time or expertise), simply use the species marked to represent “UNKNOWN” (Western Red Cedar in the example set). Identifying tree species allows the rescuer to take full advantage of the tree under consideration, rather than simply using the species with the lowest strength rating on the list (safe but conservative).

Q: What areas of the model are still uncertain, yet have significant effect on the results?

A: Model results depend significantly on the turbulence profile. The current turbulence model shows wind speed decreasing below canopy more than is probably real, which is conservative. I have both model improvements and testing in mind that might allow peeling back some conservatism, which would “turn green”slightly smaller trees as credible rescue anchors. But the differences are small, perhaps an inch or two at most in circumference. A bit of conservatism is not so bad in this technical rescue business.

Conclusion: A Healthy Tree Tells Us About the Anchor Force is Can Withstand

For regions with only light seasonal wind, limiting anchor selection to helmet-sized or larger trees is reasonable, but conservative. Using 28-inch circumference as a go/no-go criteria means that fully adequate trees would not be used. The overall rescue system may then be less effective, and less safe, for having bypassed potentially better-placed anchor trees. In areas with higher seasonal wind(wind storms greater than 45 mph), even smaller trees can be credible rescue anchors, based on having survived wind loading.

This model offers results that protect system integrity while being practically deployable in the field. These results are consistent with test data. Testing to failure is quite reasonably limited to modest forces for reasons of safety and practicality. This method extends results from field tests on small trees up to somewhat larger trees.

As always, decisions during rescue operations must align with training and field-appropriate tactics. NO SCIENCE PROJECTS DURING RESCUE MISSIONS! If teams intend to use smaller trees as rescue anchors, then practice how to do that responsibly.

The usual ITRS caveats apply here:

- More testing and research is good.

- Carefully consider new data, and apply it prudently.

- Do the right thing for your team and your mission.

If my compatriots in the technical rescue community have questions, suggestions, criticisms, or want data for particular tree species, feel free to contact me:

John Morton

Snohomish County Search & Rescue/ Everett Mountain Rescue

Email: water-rescue6@scvsar.org

Authors Note: The tree anchor strength model described here first began as a joint project between myself and Mark Miller, of Ouray Mountain Rescue and Rigging for Rescue. Mark is well known in the community of climbers, guides, and technical rescuers, including among those who frequent ITRS events. Ironically, I was working on the presentation of this material for ITRS-2015, when I received the tragic news that Mark had been killed in a fall while ice climbing. So, while Mark was part of the early work portrayed here, he was not able to review the material presented at ITRS. This is the very least among many impacts from losing our brother Mark. – JM